Observed Difference in Subduction Slopes

There is a clear and well-documented difference between the average dip of subduction zones that face east (about 27.1°) and those that face west (about 65.6°). This asymmetry has long intrigued geoscientists. Traditional explanations emphasize variations in the age and density of the subducting lithosphere—older seafloor is denser and therefore subducts at a steeper angle.

However, the Mantle Convection Rolls Model introduces an additional and complementary mechanism: the effect of Earth’s rotational velocity on the descending slab. Velocity of the subducting slab does not matter here, only the difference in rotational energy at different depths. We do not see how the tectonic plates move, but that does not mean we sould neglect the relevant calculations. In this case, calculating the difference is very simple.

Rotational Velocity and Kinetic Energy Loss

As the slab descends roughly 660 km—about one-tenth of Earth’s radius—it gradually loses rotational velocity, as the circle at surface is obviously longer then the lower circle. It therefore involves a significant kinetic-energy transfer to the surrounding mantle. If we set Earth’s radius as 1, the radius at 670 km depth is ≈ 0.9. At the equator, the difference in kinetic energy between these levels can be estimated as rotational energy at surface subtracted by rotationa energy at 670 km depth:

The result, 0.2, means that about 20% of the slab’s kinetic energy is dissipated while moving from the surface to the transition zone. Considering that the tangential velocity at the equator reaches about 1 ,674 km h⁻¹, a 20% reduction represents an immense energy transfer to the surrounding material. Imagine what happens to one cubic kilometer of slab after it loses 20% of its kinetic energy with the velocity of 1 ,674 km h⁻¹. Should it have no effect at all, or should it alter the dip of the descending slab? Of course the dip is affected by this transfer of energy, and it fits very well to the difference between the east and west of the Pacific Ocean.

The aggregate effect of this energy loss manifests differently on opposite sides of the Pacific. Along the eastern margins, the energy dissipation induces compressional pressure between converging plates; along the western margins, it produces a tensional or pulling effect. These opposing mechanical environments contribute to the observed difference in average slab dip: approximately 46° overall, with west-oriented subduction averaging near 65° and east-oriented near 27° (described in an essay by Doglioni & Panza, 2015).

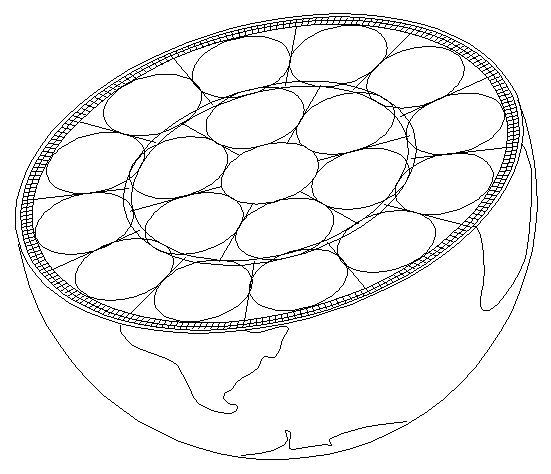

Geometric Representation

This relationship can be illustrated geometrically. If the rotational velocity at Earth’s surface is represented as u = 1 and at 660 km depth as u = 0.9, two similar triangles can be drawn to represent eastward and westward subduction. The short side of each triangle—the horizontal gap between real flow (red) and the hypothetical no-rotation line (black)—corresponds to the observed angular difference. These geometric relations visually express how differential rotational velocity produces the characteristic east–west asymmetry of slab inclination. The simple drawing below shows the average difference.

Equatorial Symmetry and Mantle Roll Alignment

The same principle extends horizontally. The main division points of the equator coincide strikingly with the division boundaries of modelled lower-mantle convection rolls, which are spaced 30° apart. When subduction zones located exactly 180° apart on the equator are compared—most notably those of South America and Indonesia—their symmetry becomes evident. The position of these two trenches opposite each other can by no means be said to be just a coincidence.

This has of course been mapped in detail for each subduction zone. In turn, those subduction zones show identical, although mirrored, deviation from true north. This symmetry can be explained by referring to the mantle convection rolls model. The fact that not only position, but also deviation from north is identical can not be said to be just a coincidence.

Integration Within the Mantle Convection Rolls Model

According to the Mantle Convection Rolls Model, the slab ultimately enters a ductile, convecting mantle where geophysical conditions are balanced. The difference in slab dip between east- and west-oriented subduction zones thus arises from the rotational-kinetic interaction between the descending plate and the mantle framework through which it moves.

Horizontally moving mantle material is similarly governed by the rotating geoid, producing predictable deviations from straight-line flow that define the roll-like geometry of convection cells. The vertical and horizontal components of this system are dynamically linked—both shaped by the same rotational gradients that influence slab inclination.The Missing Correlation Between Seafloor Age and Slab Dip

If slab dip were controlled primarily by the age of the subducting seafloor, one would expect a clear correlation between older, denser lithosphere and steeper subduction angles. However, such a relationship is not observed—particularly along the western margin of the Pacific Ocean.

For example:

- The Mariana Trench, one of the deepest and steepest subduction zones on Earth, indeed involves an old oceanic plate (>150 million years). But if seafloor age were the decisive factor, then all regions subducting comparably old crust should exhibit similar dip angles—which they do not.

- Along the Japan Trench, the subducting Pacific Plate is also very old (130–140 million years), yet its dip is far shallower in many segments, especially near Honshu and Hokkaido, where the slab inclination decreases dramatically toward the northeast.

- Conversely, some younger lithosphere—such as that near Tonga or New Britain—subducts at extremely steep angles, contradicting any simple “old plate = steep dip” rule.

In other words, no systematic correlation exists between the age of the descending seafloor and the dip angle of subduction along the western Pacific. This observation directly contradicts the density-driven model, while strongly supporting a dynamic explanation based on Earth’s rotational velocity gradients.

The striking and consistent difference between eastward- and westward-dipping slabs, on the other hand, reveals a clear global pattern that matches the expected distribution of kinetic energy within the rotating mantle.

Why Has This Explanation Been Overlooked?

It may appear surprising that such an evident physical relation—between Earth’s rotation and slab dip—has not been explicitly emphasized before. The reason may lie in the timescales involved.

When a unit volume of lithosphere, say one cubic kilometer of slab, moves downward by 100 km, it inevitably tends to drift eastward relative to the overlying surface because its rotational velocity decreases with depth. The motion is fully deterministic: the deeper the material sinks, the greater its lag relative to the surrounding mantle at that depth.

Yet this motion unfolds extremely slowly—so slowly that, within the human timeframe or even during the lifespan of an oceanic plate, the effect seems negligible. Over millions of years, however, this cumulative eastward drift becomes geophysically significant.

It alters the balance between horizontal traction and vertical descent, subtly controlling slab geometry.

Because geoscientific models typically focus on instantaneous plate velocities rather than rotational energy differentials, the long-term kinematic consequences of Earth’s rotation have been largely overlooked or treated as negligible.

Thus, the explanation first formulated here appears novel not because it contradicts known physics—but because it applies fundamental physical reasoning (rotational mechanics) across a geological timescale that previous models rarely considered in full.

Conclusion

The consistent difference in dip angle between east- and west-oriented subduction zones can therefore be interpreted as a manifestation of Earth’s rotational dynamics coupled with the internal organization of mantle convection rolls. This integrated view connects global rotation, energy dissipation, and large-scale convection geometry into one coherent framework, offering an explanation that aligns observed slab asymmetry with measurable physical principles.

The geometry of subduction zones—both in terms of dip angle and global distribution—reflects the interaction between Earth’s rotation, kinetic energy dissipation, and large-scale mantle convection rolls.The absence of any correlation between seafloor age and slab dip across the western Pacific undermines the traditional density-based explanation. Instead, the consistent and global asymmetry between eastward and westward subduction aligns naturally with the physics of a rotating planet, where angular momentum and kinetic energy vary systematically with depth and latitude.What may initially appear as asymmetric behavior of tectonic plates can thus be understood as a predictable consequence of rotational mechanics acting within a viscous, convecting mantle—an effect long hidden simply because of its subtlety and timescale.