When we look at Earth’s surface, it’s easy to get lost in the details of coastlines, mountain ranges, rivers, and ridges. But if we step back and think about the planet’s deeper structure, something fascinating emerges: a repeating pattern along the Equator that follows 30° intervals.Why does this matter? Because these intervals may reflect the way Earth’s mantle moves beneath our feet.30°: A Hidden Rhythm of the Earth

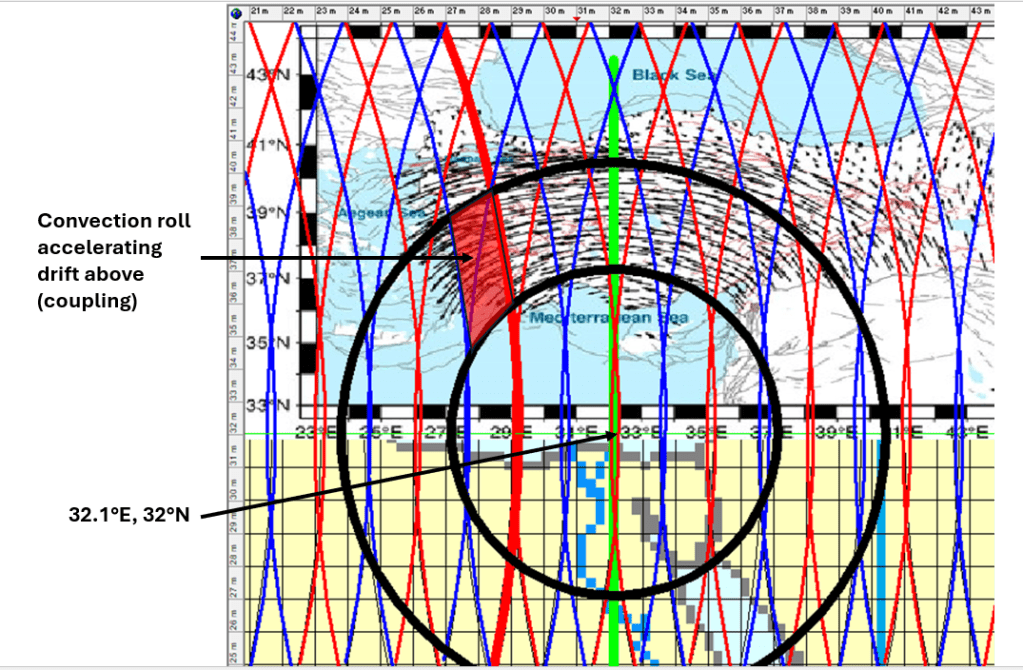

Here’s the basic observation: the distance from a continental coastline to the nearest mid-ocean ridge along the Equator is 30° in a repetitive way. That number also shows up inside Earth, as the depth from the upper mantle down to the boundary above the outer core (the Gutenberg discontinuity) corresponds to the same span if you measure it along the Equator.

In other words, Earth seems to “prefer” structures that fit into neat 30° chunks, both at the surface and deep inside.

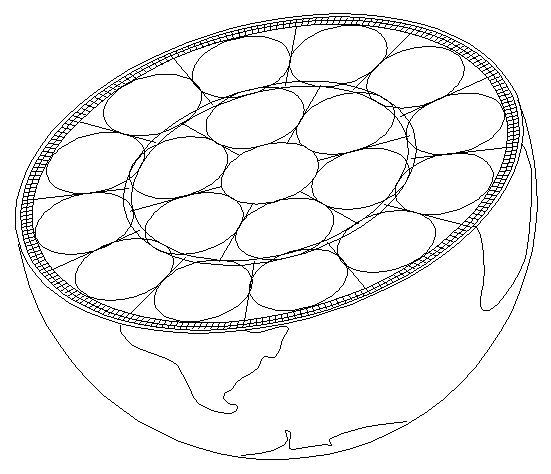

This suggests that mantle convection rolls, the giant slow-moving currents that circulate heat within the Earth, might be about as tall as they are wide, filling out the relevant space like building blocks.

Do These Rolls Really Exist?

We can’t measure mantle convection rolls directly, only thickness of Earth’s layers. But if the theory holds, then we should see their influence on the surface. One way to test this idea is to trace the Equator step by step and look at how major features line up.

Step by Step Along the Equator

If we follow the Equator around the globe, we can divide it into roughly 30° segments. Each of these intervals is marked by a major geologic boundary — a coastline, ridge, or rift. Here’s how it looks:

- East Pacific Rise → West Coast of South America

The East Pacific Rise is one of the fastest-spreading mid-ocean ridges on Earth. About 30° west lies the subduction zone of the Andes, where the ocean floor sinks beneath the continent, fueling earthquakes and volcanoes. - West Coast of South America → East Coast of South America

Crossing the continent, we move from the dramatic tectonic activity of the Pacific margin to the quieter Atlantic side. This stretch includes the Amazon Basin, with its massive river system, which itself aligns closely with the 30° spacing. - East Coast of South America → Mid-Atlantic Ridge

The Atlantic Ocean opens here, with the Mid-Atlantic Ridge running down its center. This ridge is part of the global rift system, where magma rises to form new ocean floor. - Mid-Atlantic Ridge → East Coast of Africa

Another 30° step brings us to the African coastline, which mirrors South America’s. This pairing reflects the ancient breakup of Gondwana, a perfect example of how mantle flow leaves a lasting imprint on surface geography. - East Coast of Africa → Great Rift Valley

The East African margin lies above mantle upwellings. Just 30° inland, the Great Rift Valley splits the continent, an active rift zone where the crust is being pulled apart and new oceans may someday form. - Great Rift Valley → Mid-Indian Ridge

Continuing eastward, the Equator crosses the Indian Ocean, where the Mid-Indian Ridge rises. Like other spreading centers, it’s a direct expression of convection currents pushing Earth’s plates apart. - Mid-Indian Ridge → East Coast of Indonesia

Here the Equator traverses a broad ocean basin before reaching Indonesia. This region sits at the collision of several tectonic plates, where subduction and volcanism dominate. - East Coast of Indonesia → West Coast of Indonesia

Within just 30°, we pass across one of the most tectonically active areas in the world. Subduction zones border both sides of Indonesia, creating a chain of volcanoes and frequent earthquakes.

The Pacific Exception

One striking difference emerges in the Pacific Ocean. Unlike the Atlantic or Indian Oceans, the Pacific has no continental landmass near its center. Hawaii, located north of the Equator, lies above a lower mantle division line according to the comprehensive convection rolls model, but not on the Equator itself.

This means the Pacific spans a much wider interval: about 150° from Indonesia to South America, or 120° from Indonesia to the East Pacific Rise. At the Equator, the East Coast of Indonesia and the West Coast of South America mark the outer edges of the Ring of Fire. From those two points, subduction zones stretch in a regular arc all around the Pacific Basin.

In this sense, the Pacific doesn’t break the pattern, it expands it. The Equator provides the framework for tracing the boundaries, while the Pacific demonstrates how convection rolls and plate boundaries can extend into even larger structures.

Coincidence… or Deep Structure?

Is this just chance? Statistically, it seems unlikely that so many major boundaries would fall into such regular intervals. If we consider tectonic drift, the slow movement of continents and oceans over millions of years, the fact that we see such symmetry today is even more striking.

But once we think about the mantle’s convection rolls, the puzzle pieces start to fit. The surface divisions may simply be echoes of these massive, deep-seated currents.

Beauty in Regularity

Some of Earth’s most famous features fall right on these boundaries:

- The Great Rift Valley in East Africa.

- The Amazon River estuary in South America.

- Subduction zones along the Andes Mountains.

- The converging coasts and volcanic arcs of Indonesia.

- And the sweeping Ring of Fire, stretching from South America to Indonesia.

Even the north-south symmetry of the Atlantic Ocean fits into the pattern. When you look at a world map with this in mind, it’s hard not to see a hidden order, a kind of natural geometry that shapes both land and sea.

Why It Matters

This isn’t just an exercise in pattern-spotting. If convection rolls in the mantle really do leave their fingerprint on the surface at 30° intervals, then studying these divisions could help us understand Earth’s inner workings more deeply.

It’s a reminder that the beauty of our planet isn’t only in mountains and oceans, but also in the invisible rhythms of the deep Earth that quietly shape them.