The Snæfellsnes Peninsula is a particularly remarkable region of Iceland because it hosts three distinct volcanic systems aligned roughly east–west across the peninsula. Two of these systems have very similar names. The easternmost system is Ljósufjöll, and the central one is Lýsufjöll. Both names carry essentially the same meaning: “the light-coloured mountains.”

This name refers to the relatively silica-rich rock types found in these systems. Compared to many other volcanic areas in Iceland that are dominated by darker basaltic compositions, these systems contain a higher proportion of evolved, more silicate-rich rocks. The lighter coloration of the rhyolitic and dacitic components gives the mountain ranges their distinctive appearance and explains the origin of the names.

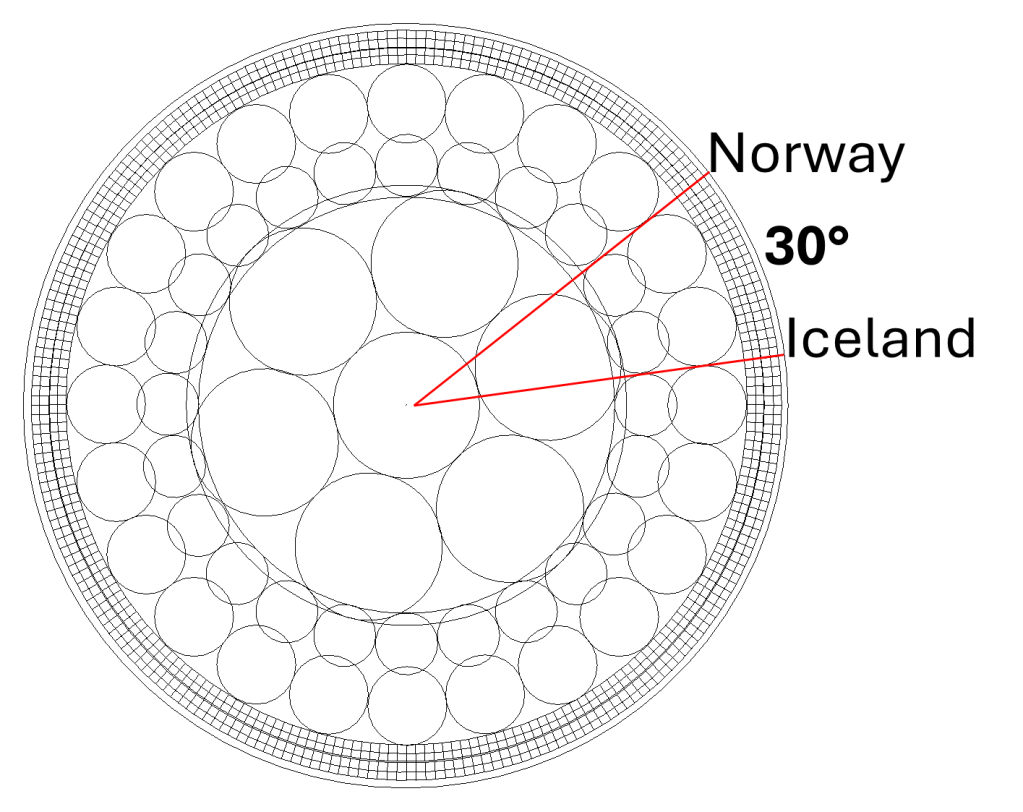

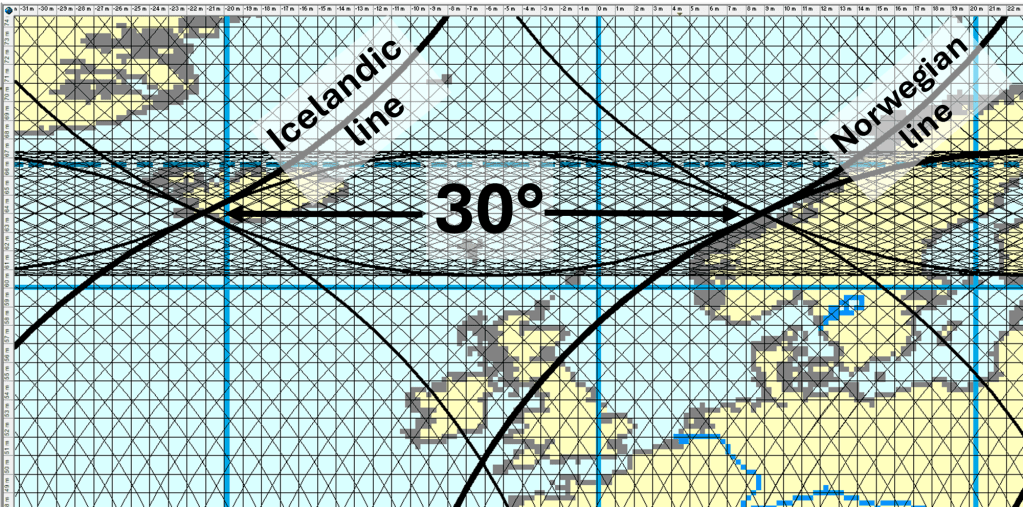

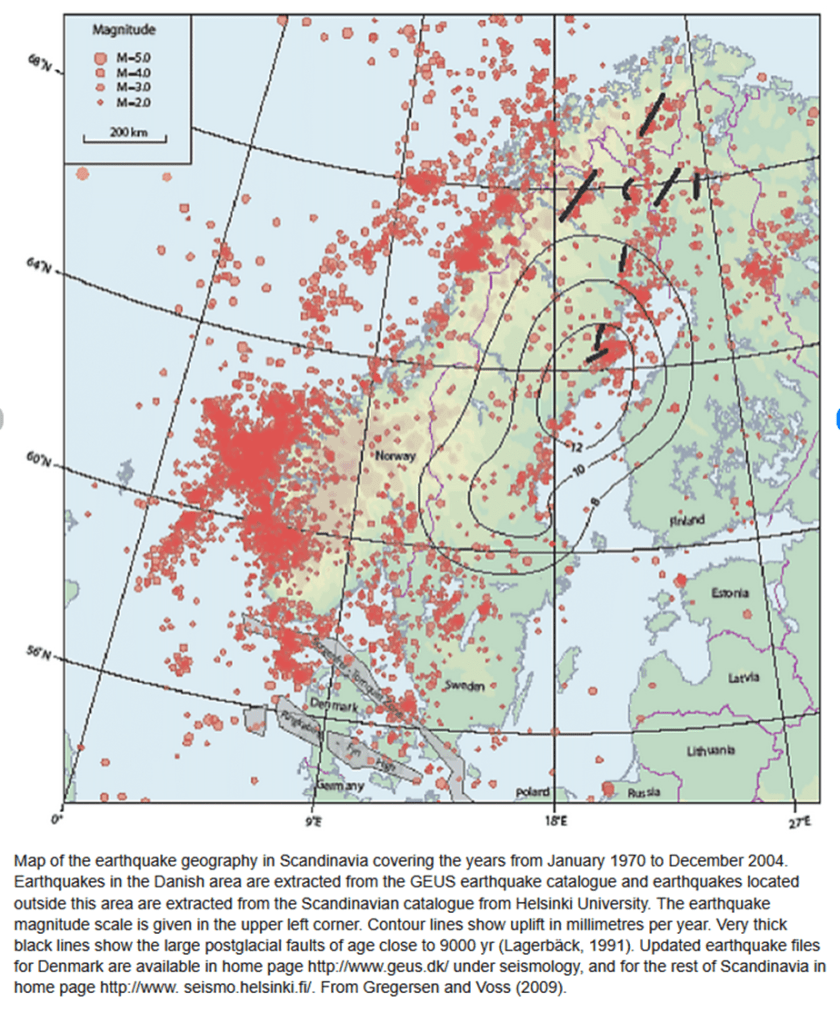

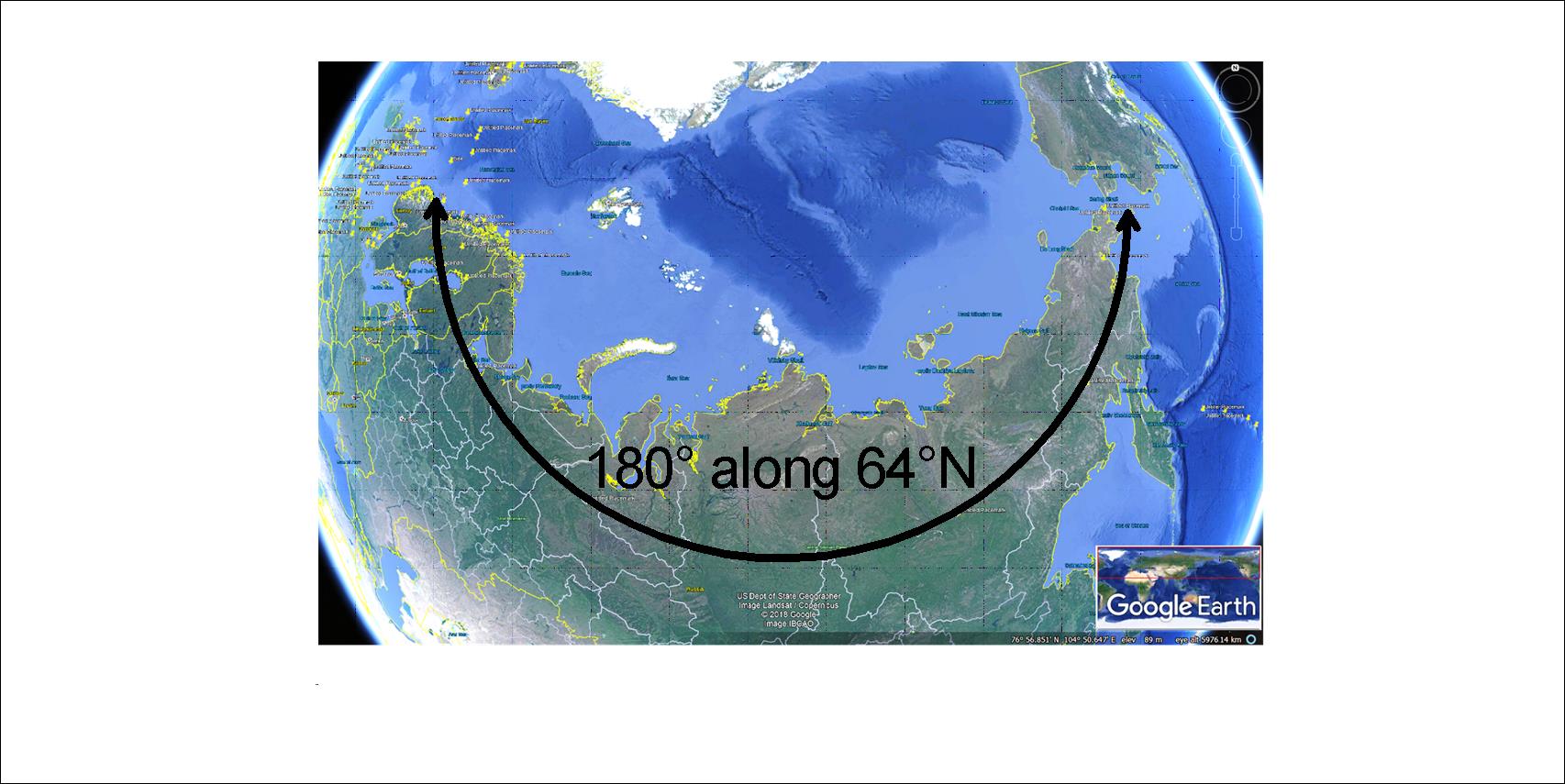

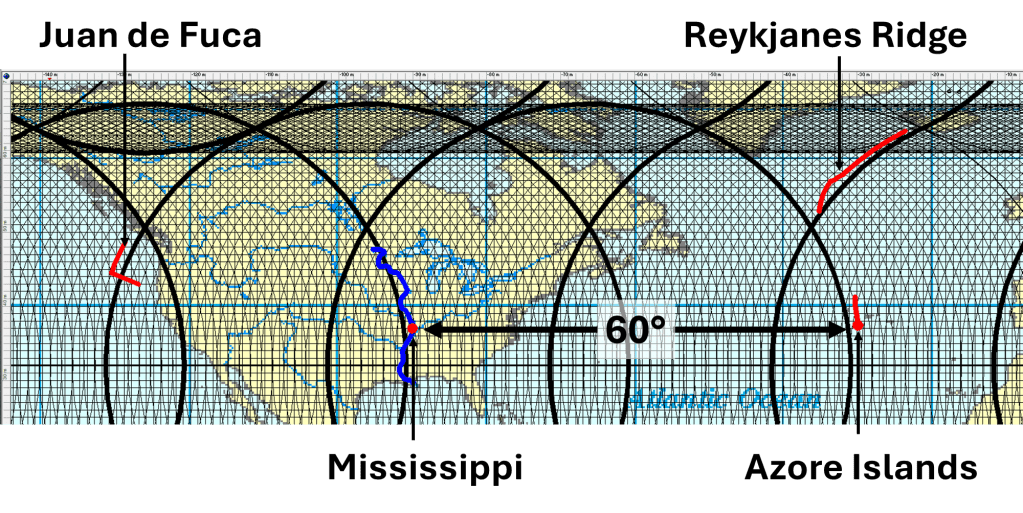

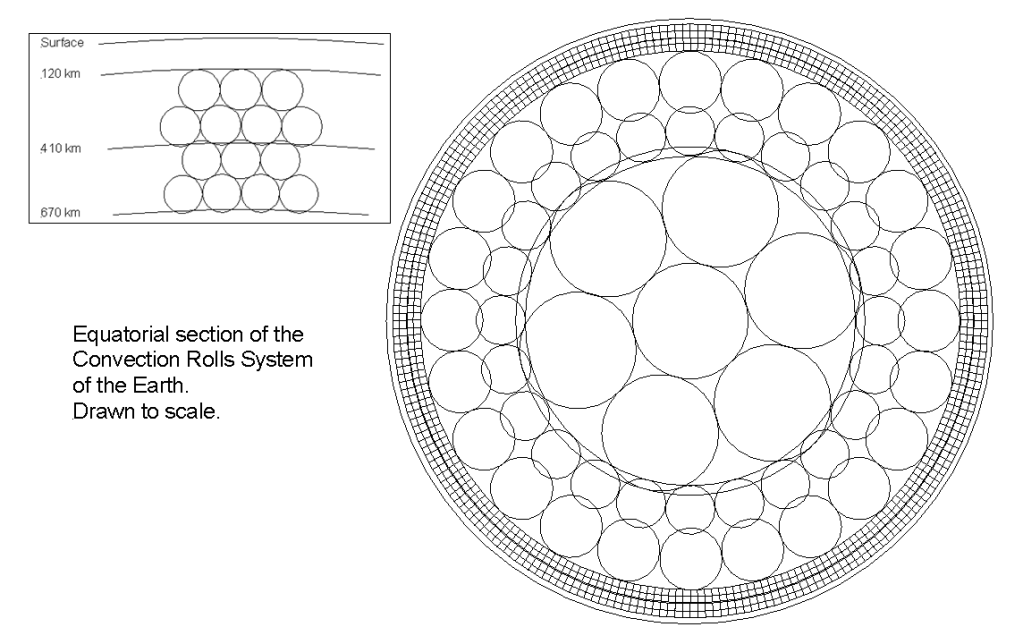

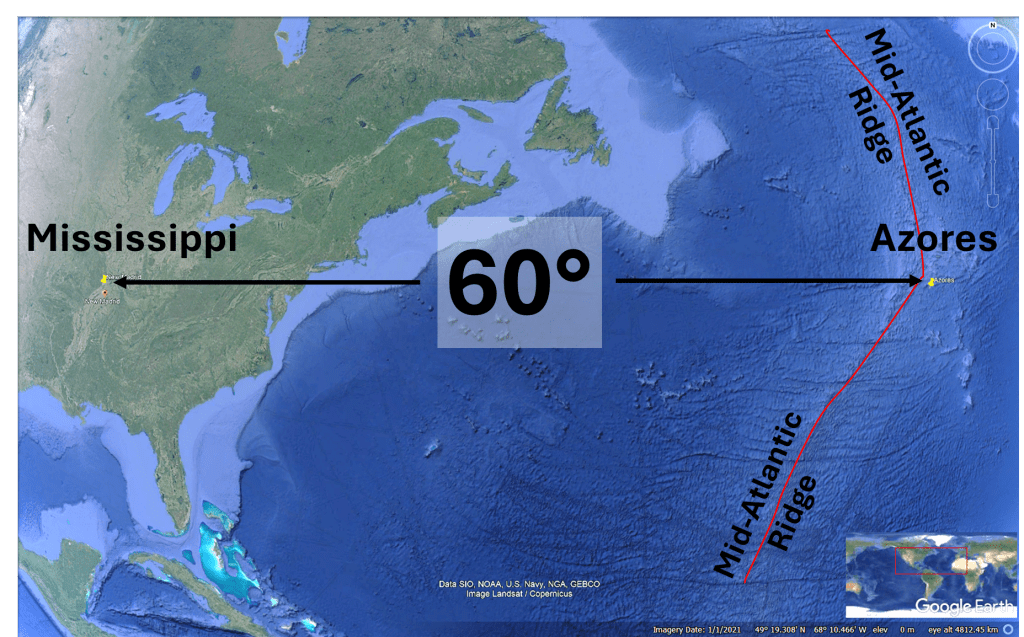

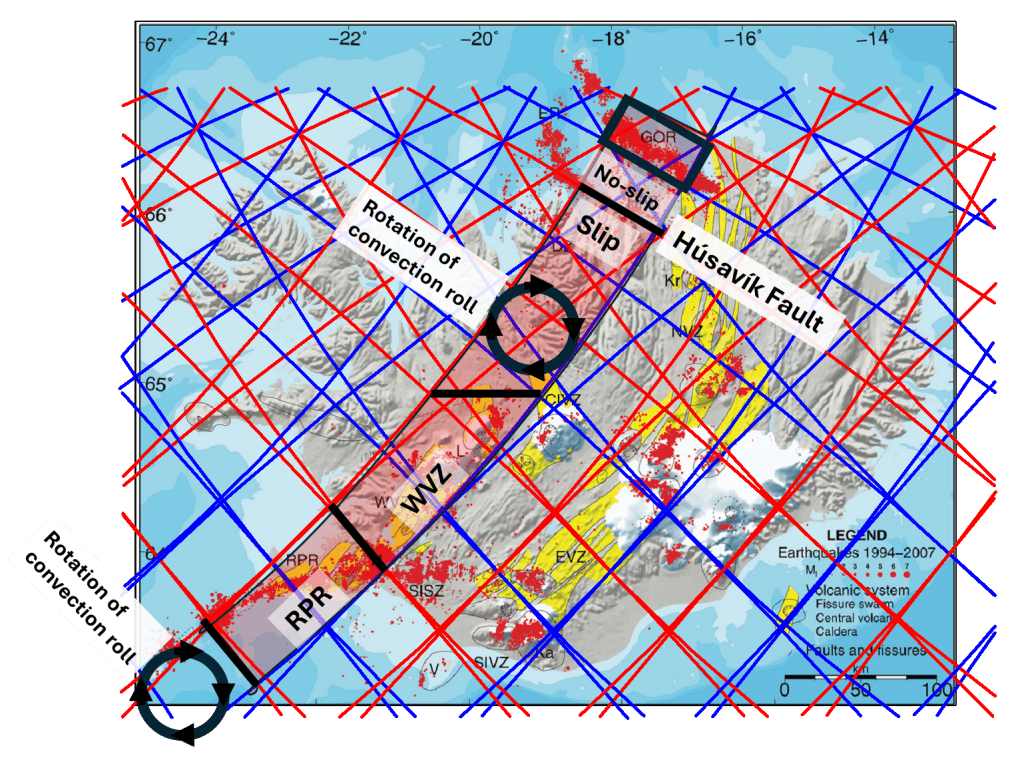

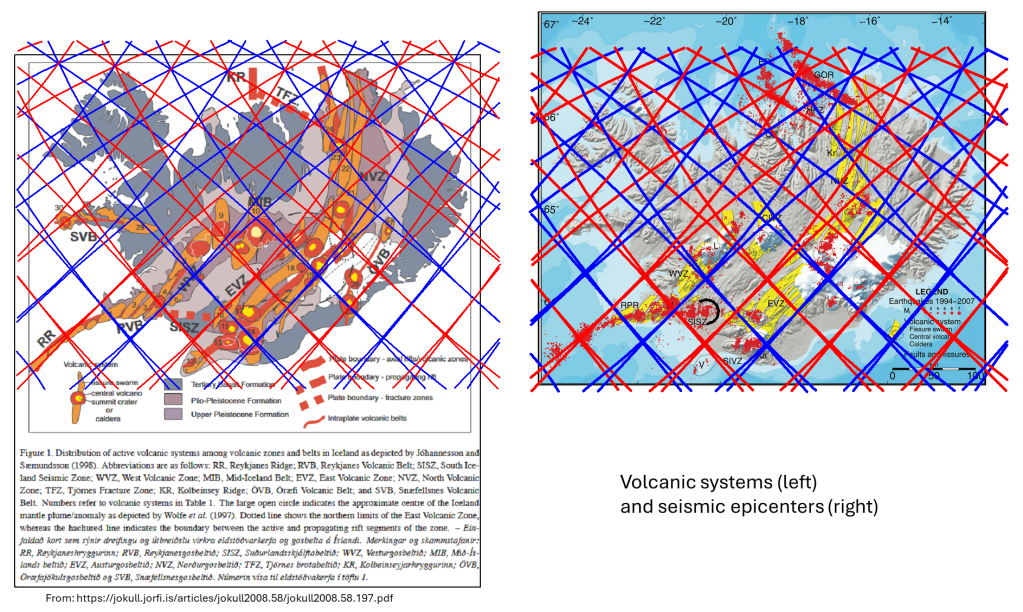

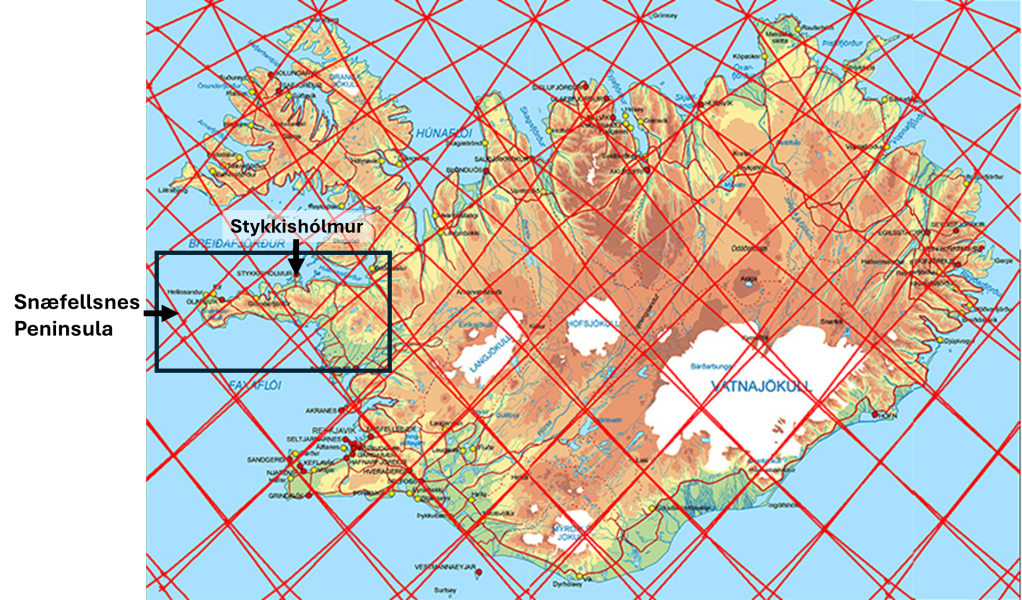

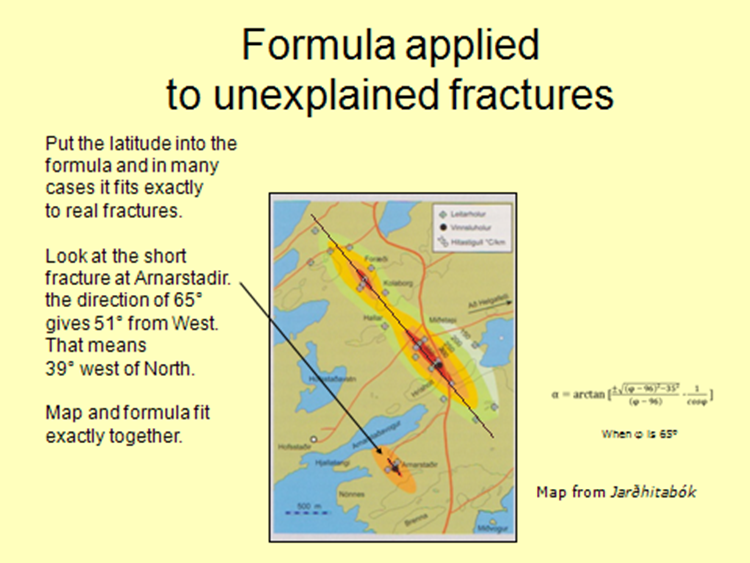

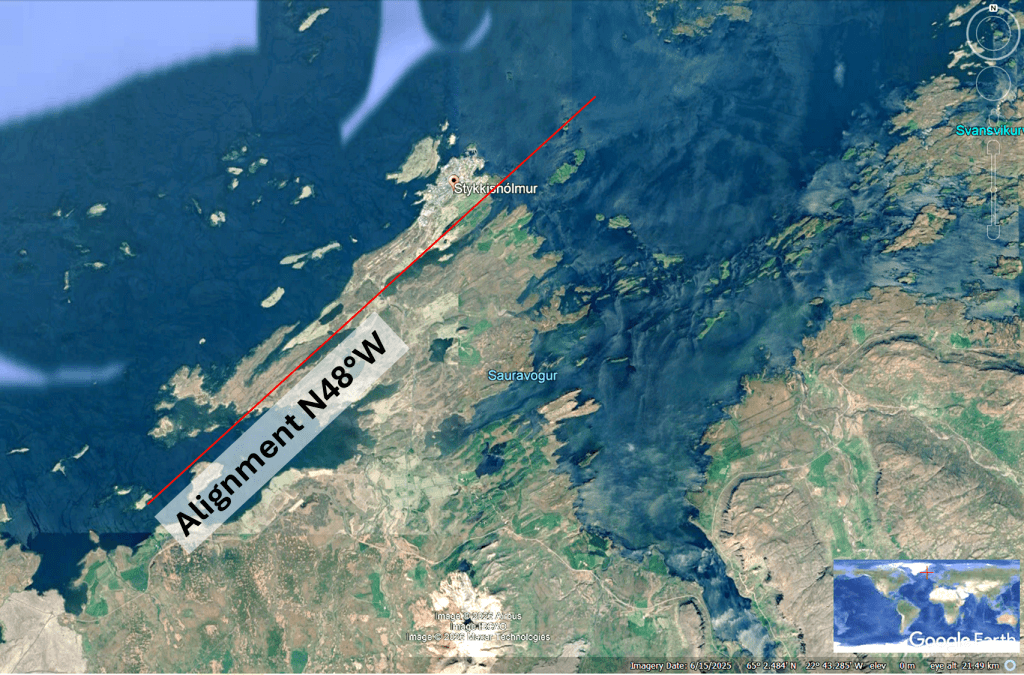

An additional noteworthy feature lies beneath the town of Stykkishólmur. The town receives geothermal hot water from a fracture zone whose orientation corresponds closely with predicted structural alignments derived from the convection rolls model of mantle flow. According to this interpretation, a deep-seated division line, representing a boundary between adjacent long convection rolls in the mantle, generated stress conditions favorable for fracture formation in the overlying crust. The present-day geothermal circulation would then be a surface expression of this deeper structural control.

At the same time, the surface morphology of the peninsula has been strongly modified by repeated glaciations. Glacial erosion has carved valleys and lineaments that follow a different dominant alignment. Interestingly, this second alignment also corresponds to another predicted set of division lines within the convection rolls model. In other words, both the geothermal fracture system and the glacially sculpted surface features appear to reflect deep structural patterns rooted in mantle convection dynamics.

Taken together, the volcanic distribution, geothermal fracture orientation, and glacial lineaments on the Snæfellsnes Peninsula may therefore represent multiple surface expressions of a deeper, organized mantle flow structure.

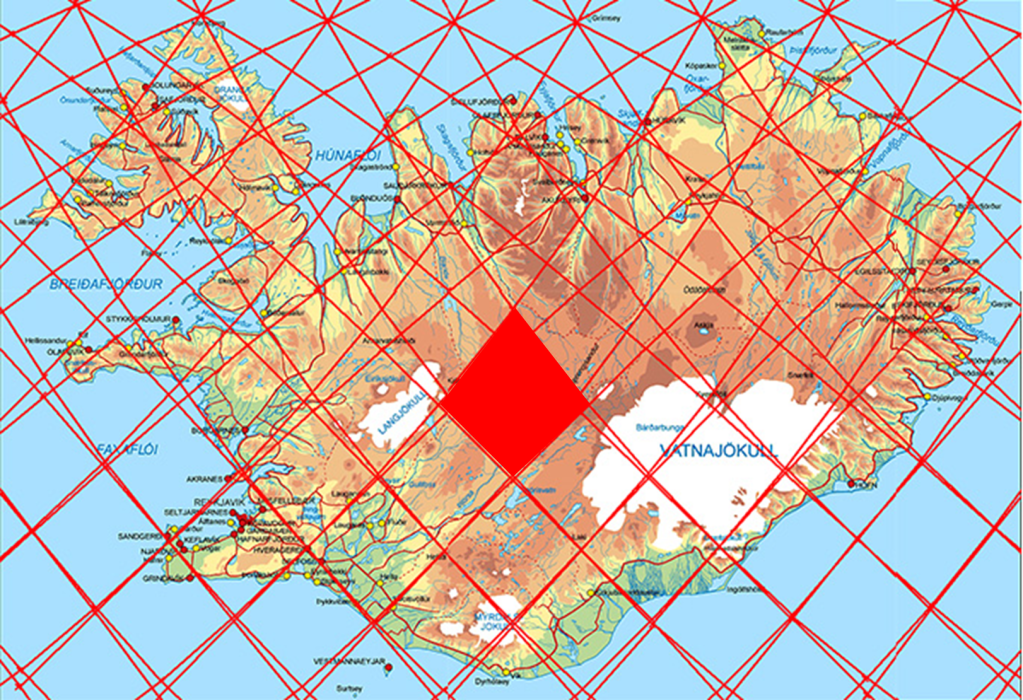

The town of Stykkishólmur:

Here it is on the map:

The town is heated with water from this fracture:

The surface is shaped according to another set of lines, also to be calculated:

On the westernmost tip of the Snæfellsnes Peninsula, Snæfellsjökull rises prominently above the surrounding landscape. This glacier-capped stratovolcano dominates the region both visually and geologically, forming a dramatic landmark at the edge of the Atlantic Ocean. Its symmetrical form and ice-covered summit make it one of Iceland’s most recognizable volcanoes.

Near its slopes once stood the home of Guðríður Þorbjarnardóttir, one of the most remarkable women of the Viking Age. Around the year 1000, she traveled with her husband to Vinland, where she lived for three years. During that time, she gave birth to her son, Snorri Þorfinnsson, who is considered the first European child born in the New World. Vinland is the old Icelandic name of the part of North America found south of Helluland (Baffinland) and Markland (Labrador), centuries before Columbus sailed over the Atlantic Ocean.

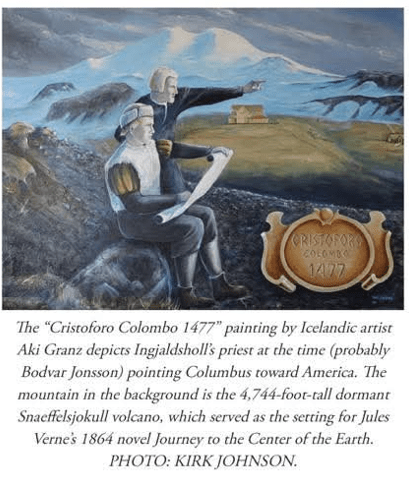

On the other side of the glacier, this painting shows Columbus in Iceland:

Behind them rises Snæfellsjökull, the glacier-capped volcano that inspired Journey to the Center of the Earth by Jules Verne. In Verne’s novel, the entrance to Earth’s interior is hidden within the crater of Snæfellsjökull, transforming this already dramatic volcano into a literary gateway to the planet’s deepest mysteries.