The transfer of heat from Earth’s core to its surface is one of the fundamental processes driving our planet’s dynamics. The temperature difference is immense: the inner core is estimated to be hotter than the surface of the Sun, while the overlying mantle is several thousand degrees cooler. This gradient is sustained because radioactive heat sources are distributed unevenly within Earth’s interior.

Radioactive elements such as uranium, thorium, and potassium are concentrated mainly in the crust and upper mantle. They are chemically incompatible with the iron–nickel alloy that makes up the core and therefore absent from the deep metallic layers. As a result, the core itself does not produce radiogenic heat.

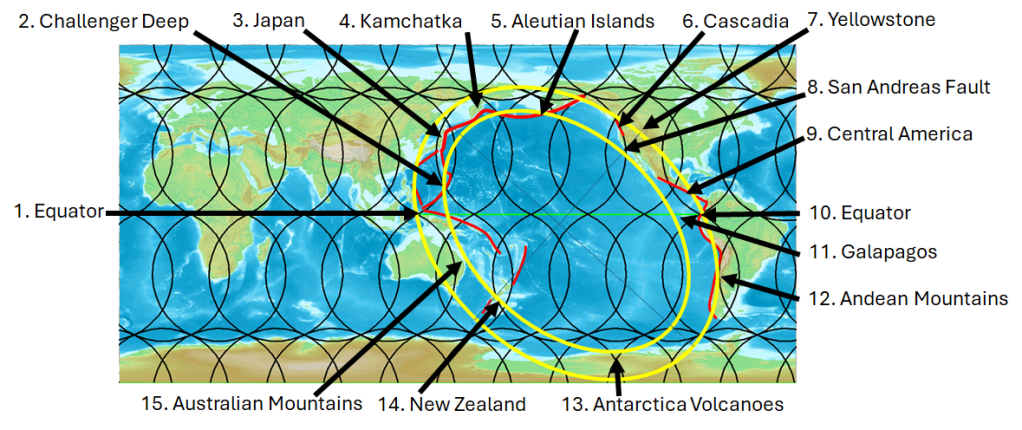

Surrounding the inner core, the outer core is a liquid metal where there is quite obviously space for six different convection cells, shown in countless drawings found in geophysical literature. At the boundary between the outer core and the mantle, the Gutenberg discontinuity, heat is transferred into the lowermost mantle.

The mantle is said to be plastic, because it is balancing between solid and liquid state. On geological timescales it behaves as a very slow, viscous fluid. This allows it to circulate, with hot material rising and cooler material sinking in enormous mantle convection rolls. Such convection provides an efficient mechanism for transferring heat from the deep Earth toward the lithosphere. When this heat reaches the lithosphere, the situation changes. The lithosphere, comprising the tectonic plates, is rigid and brittle. Here, heat can no longer be transferred effectively by convection; instead, it passes upward by thermal conduction, producing the steep geothermal gradient observed in the upper crust.

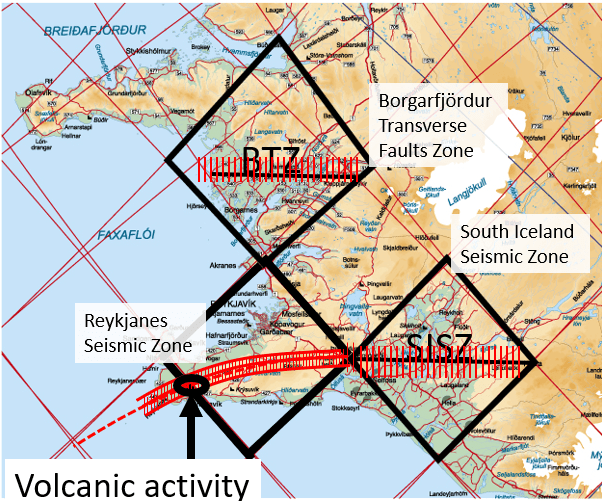

At certain boundaries, such as mid-ocean ridges, rift zones, and volcanic hotspots, mantle convection currents concentrate and channel heat more directly to the surface. Where two convection rolls meet, the focused upwelling of heat and pressure can act in a way somewhat comparable to the Munroe effect known from the physics of shaped charges: energy becomes concentrated along a narrow path, enabling molten rock to rise through the crust. This focused delivery of heat and magma helps explain the occurrence of volcanism at structurally weak points in the lithosphere.

Heat Radiation and the Core’s High Temperature

An additional factor that deserves close attention is the role of thermal radiation from radioactive elements in the upper mantle and crust. While radiogenic isotopes are unevenly distributed, their heat production is substantial, and the resulting radiation does not remain confined to local surroundings. Laboratory studies have shown that the thermal conductivity of mantle materials increases strongly at high temperatures. This implies that radiative transfer of heat through the mantle becomes increasingly significant under deep-Earth conditions.

From this standpoint, it is logical to consider that heat radiation generated in the upper mantle and crust can reach all the way down to the inner core. This view challenges the traditional assumption that the mantle acts only as an insulating blanket that slows cooling of the core. Instead, the mantle may also act as a medium that allows long-range transfer of radiative energy into the deepest interior.

This has important consequences for how we interpret the origin of Earth’s core heat. Physicists such as Max Planck calculated that if Earth’s interior relied solely on primordial heat left over from accretion, that heat should have dissipated very quickly relative to Earth’s 4.5-billion-year age. By this reasoning, the amount of primordial heat still retained in the core today must be negligible. Similarly, if downward heat radiation from the mantle is sufficient to maintain the core at high temperatures, then the release of latent heat from inner core crystallization also becomes only a minor contribution.

The conventional models that invoke secular cooling and crystallization as the dominant heat sources are understandable, given the historical focus on conduction and convection. However, they do not fully account for the efficiency of radiative transfer in high-temperature mantle materials. My analysis therefore leads to the conclusion that the extraordinarily high temperature of the core can be explained almost entirely by heat radiation from radioactive elements in the upper layers of the Earth. Rather than being a passive reservoir of slowly fading primordial heat, the core is actively sustained by radiative energy generated above it.

Convection and Radiative Balance

This interpretation also reframes how we understand convection within Earth’s main layers. The mantle, outer core, and even the inner core’s boundary layers all fit the geometric conditions for Rayleigh–Bénard type convection to occur: a fluid or semi-fluid medium heated from below (or internally) and cooled from above. For such convection to remain stable over geological timescales, the rate of convective circulation must stay perfectly balanced with the intensity of heat radiation reaching the inner core.

In other words, the deep Earth operates as a finely tuned thermal engine. Radiative input from above sustains the temperature of the core, while convection in the mantle and core ensures the continuous upward transport of heat. This delicate balance drives plate tectonics, fuels volcanic activity, and maintains the dynamic processes that have shaped Earth for billions of years.