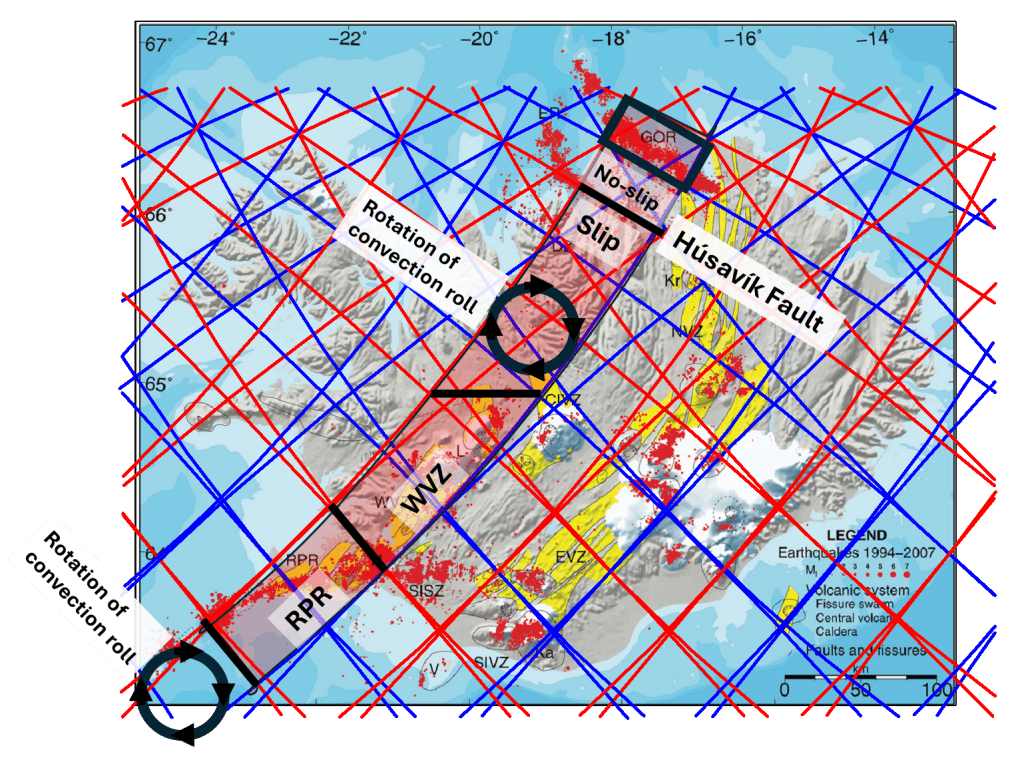

The two major fissure eruptions of Eldgjá (939 CE) and Laki (1783 CE) display several striking similarities. The eruptive fissures are broadly parallel and occur within the same general region of southern Iceland. Lava from the Laki eruption partly overlies lava produced during the earlier Eldgjá event..

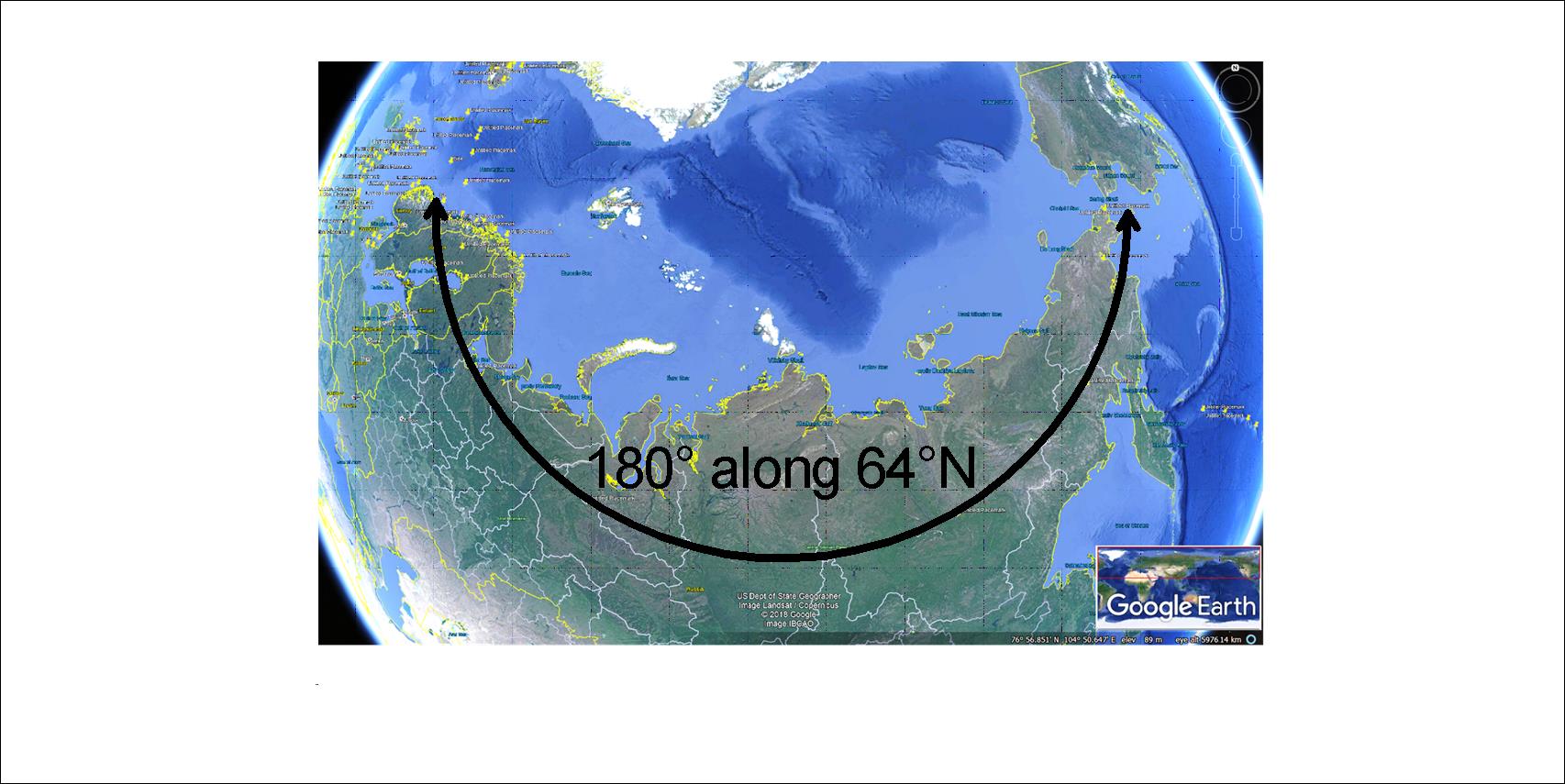

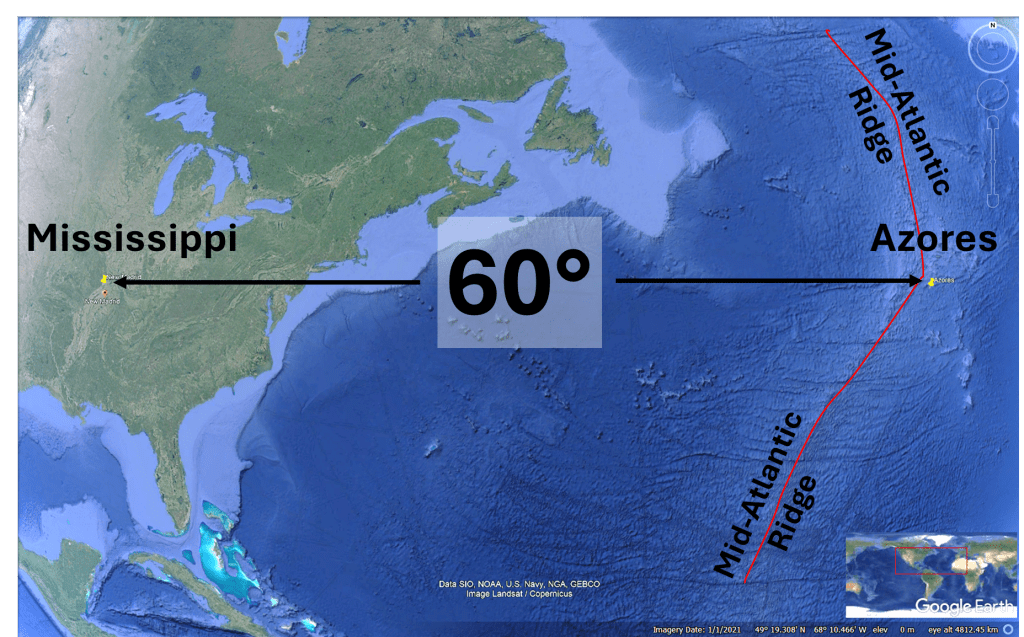

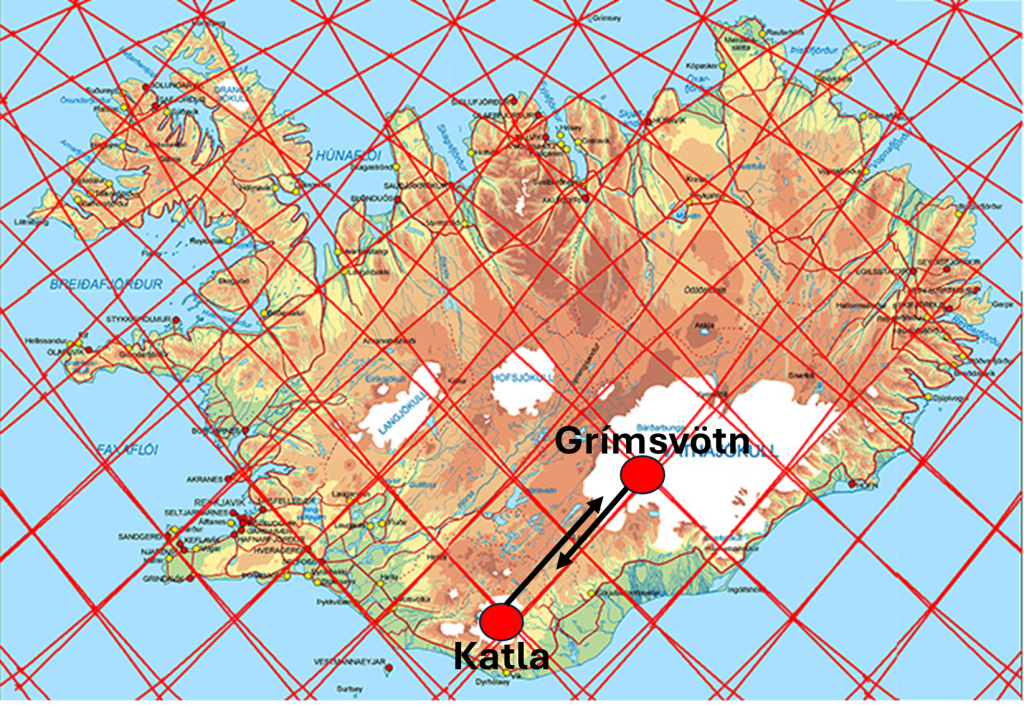

Despite these similarities, the eruptions are associated with different volcanic systems. The Eldgjá eruption is linked to the Katla volcanic system, whereas the Laki eruption belongs to the Grímsvötn system. These central volcanoes are separated by approximately 120 km. Remarkably, the Laki crater row lies almost exactly midway between the two calderas.

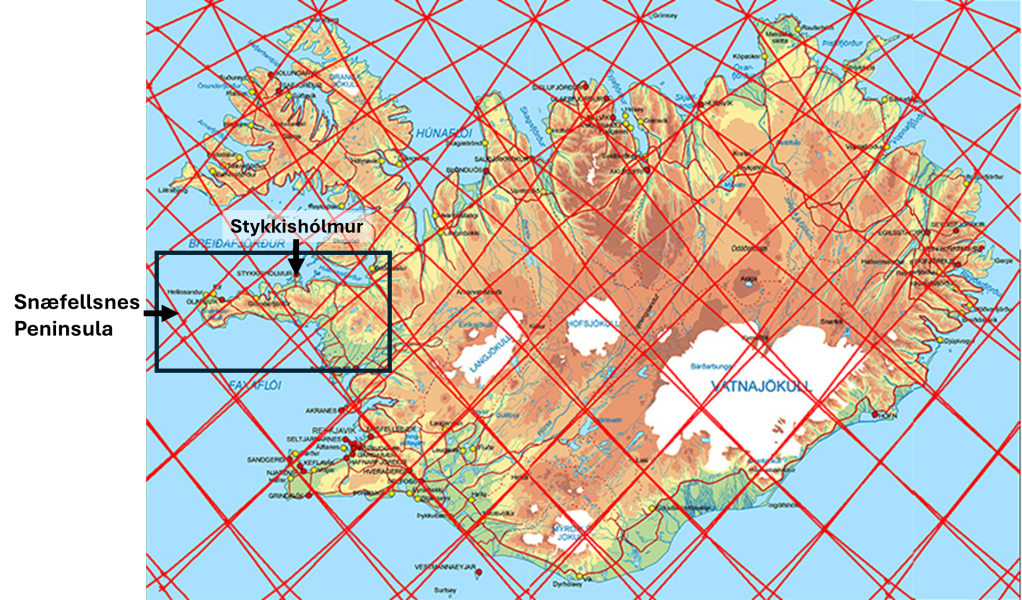

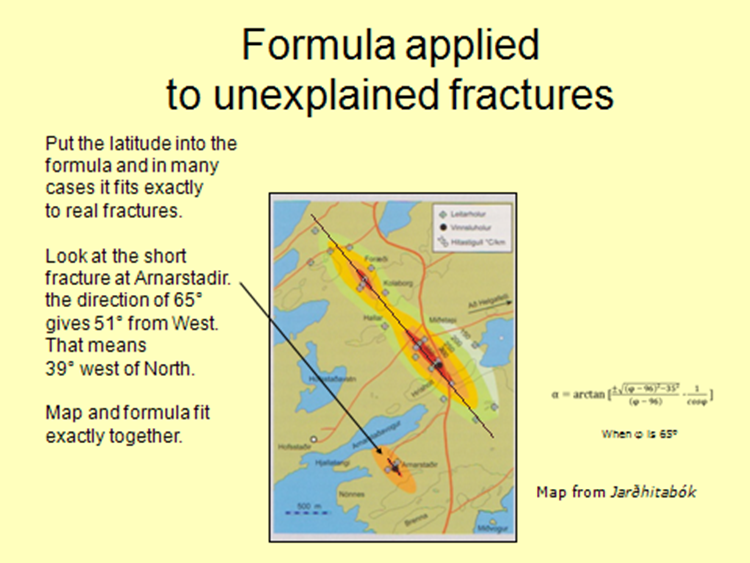

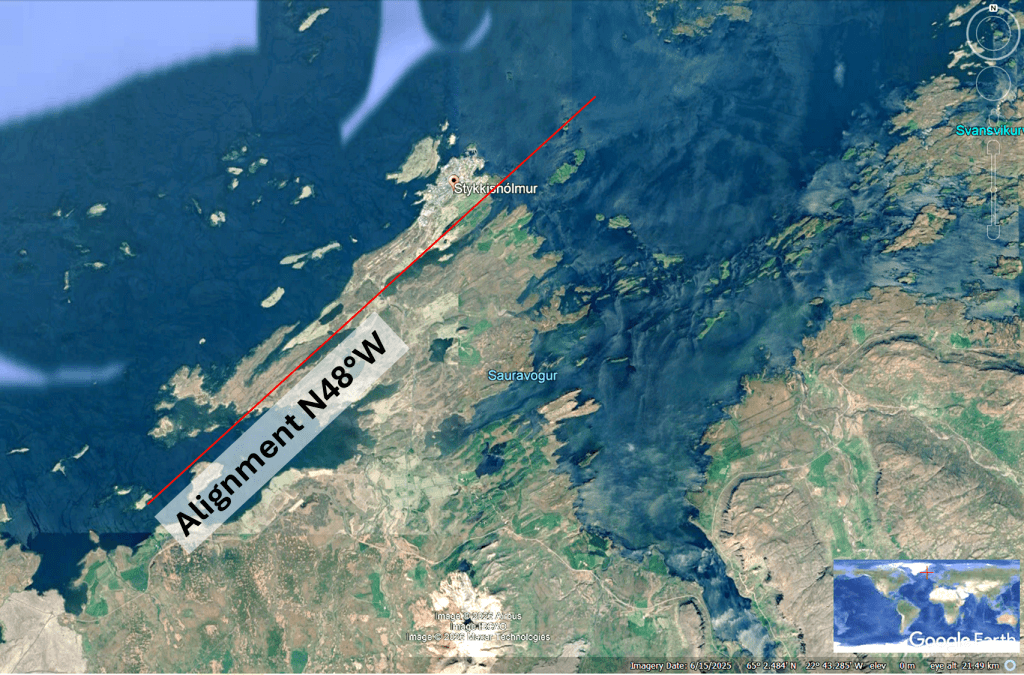

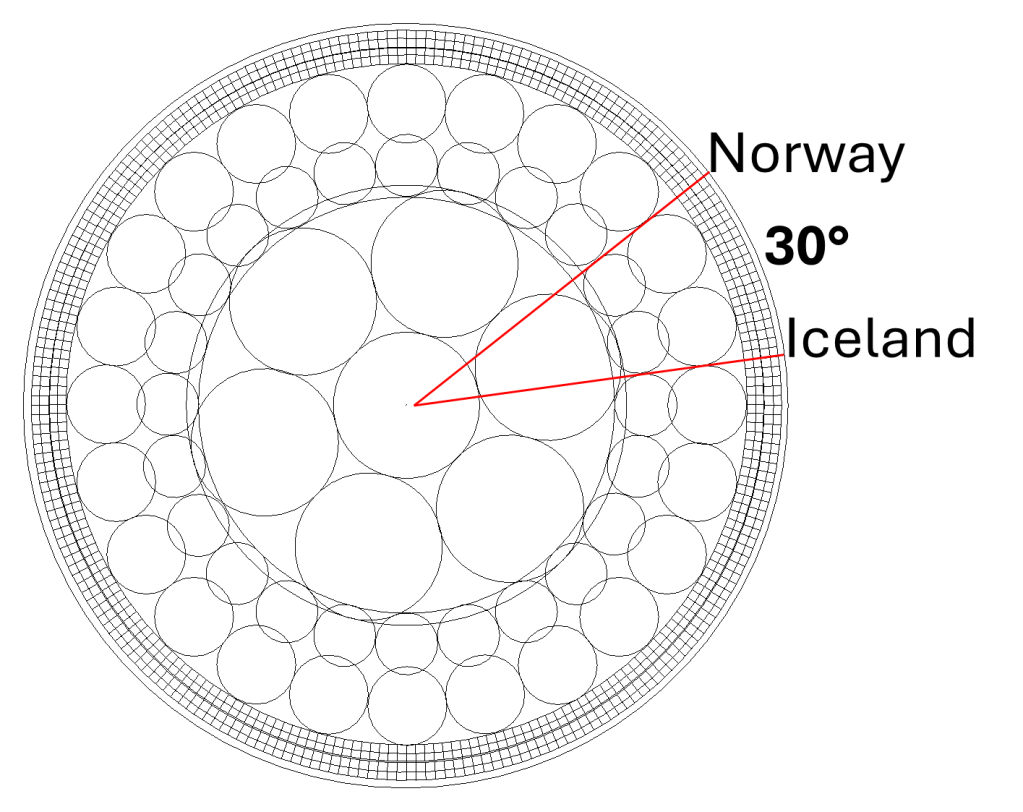

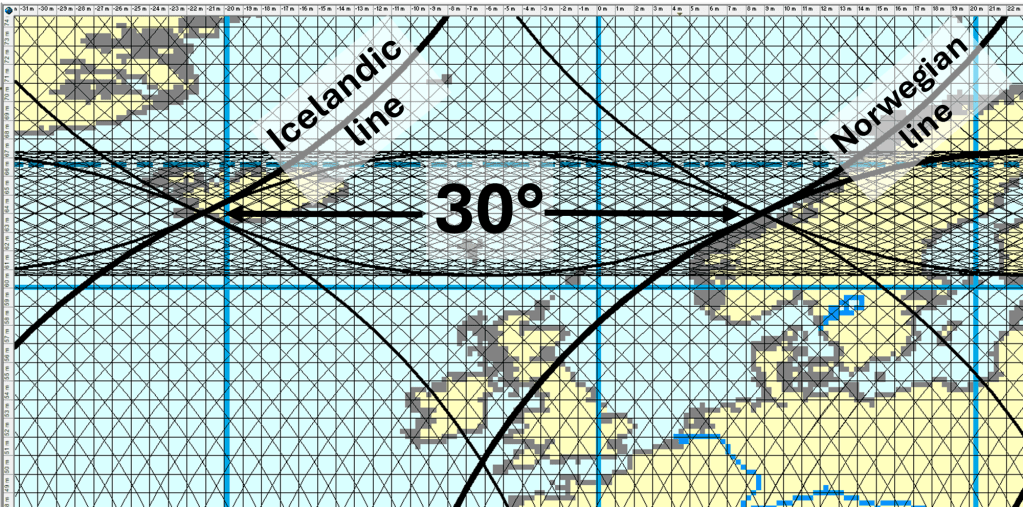

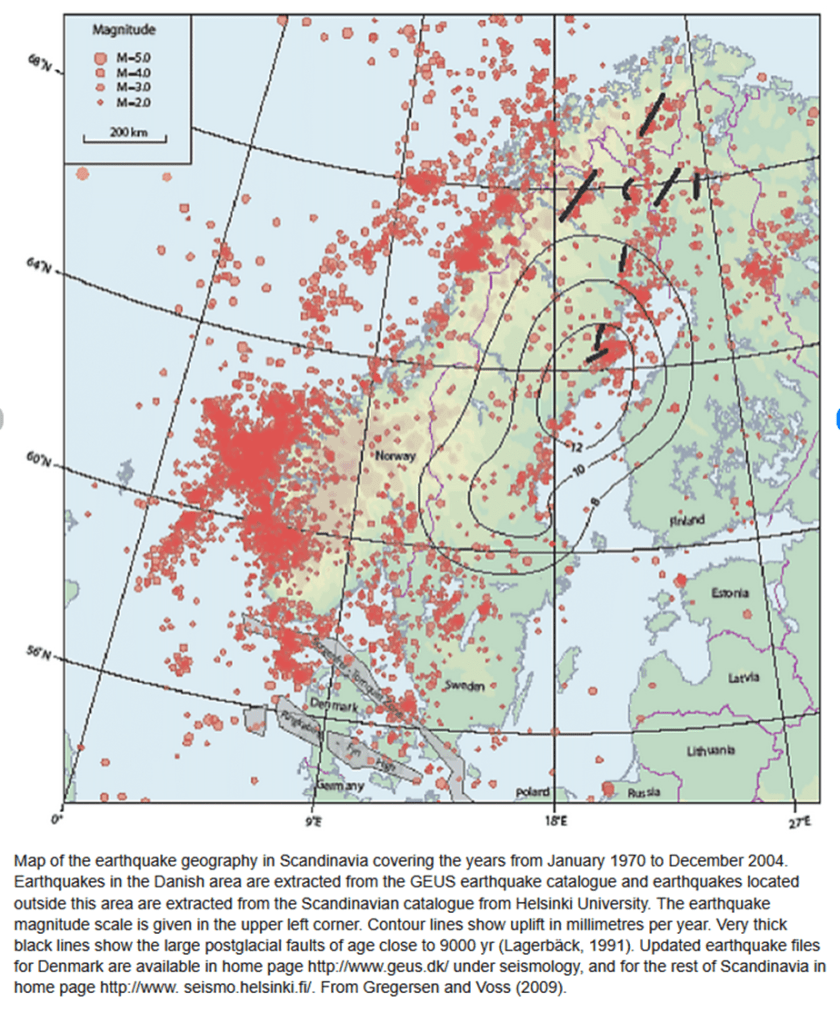

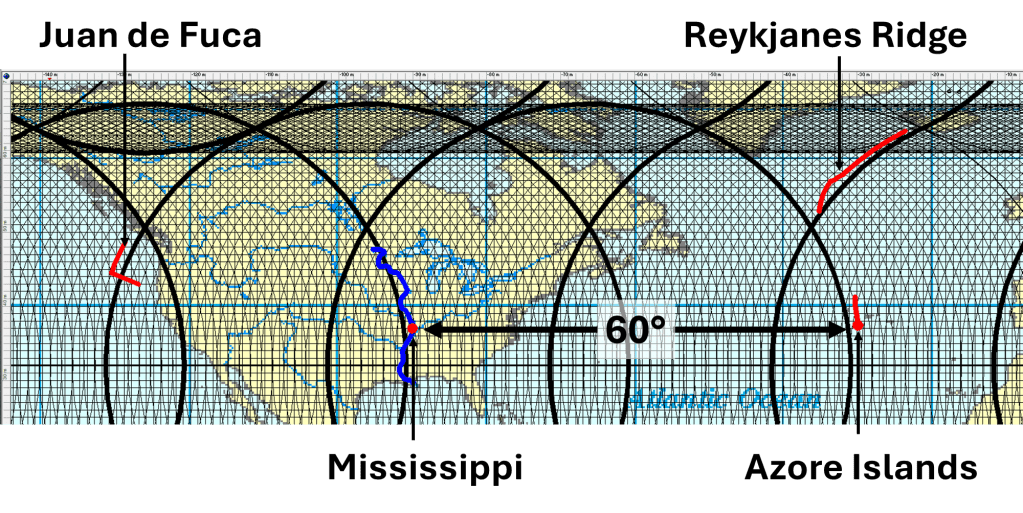

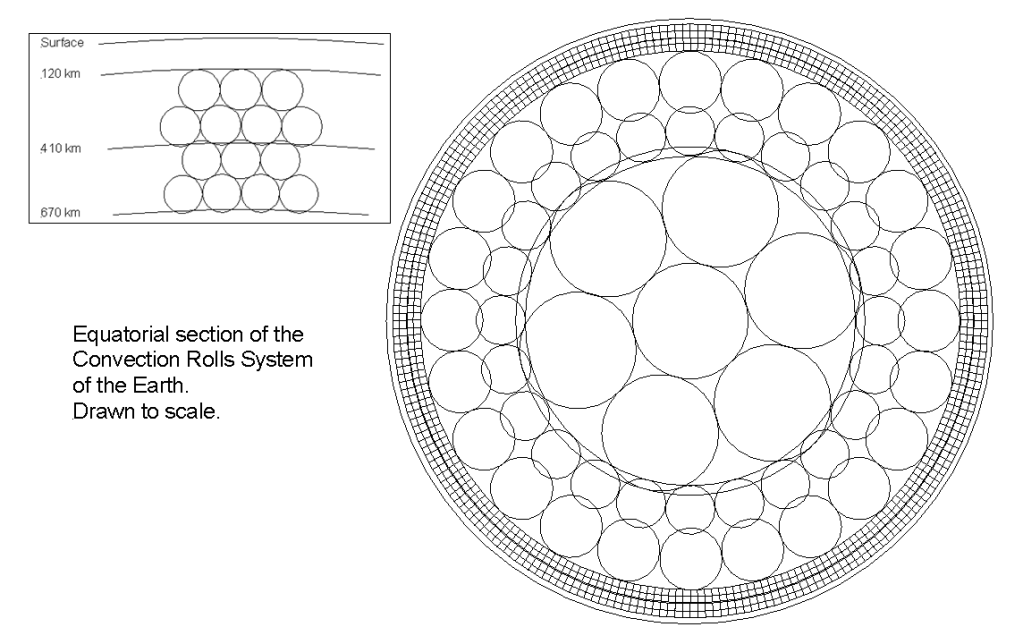

Both calderas also coincide with intersections of the structural division lines shown on the map. The dykes responsible for the eruptions propagated along the structural line situated between the two calderas, forming fissures that follow the same general orientation. This geometry shows that the regional stress field and crustal structure guide magma transport over large distances.

In both cases, the propagating dyke appears to cross a perpendicular structural division located between the two volcanic systems. The onset of eruption occurs shortly after this crossing. This recurring pattern suggests that the intersection between these structural elements plays an important role in controlling where magma reaches the surface.

One interpretation is that the perpendicular division represents a zone of enhanced crustal permeability, where fractures or weaknesses allow magma within the dyke to ascend more easily. Another possibility is that this structural boundary marks a deeper source region where additional hot magma is supplied from below. In this case, the propagating dyke may intersect a region of increased magma pressure or temperature, destabilizing the system and triggering eruption.

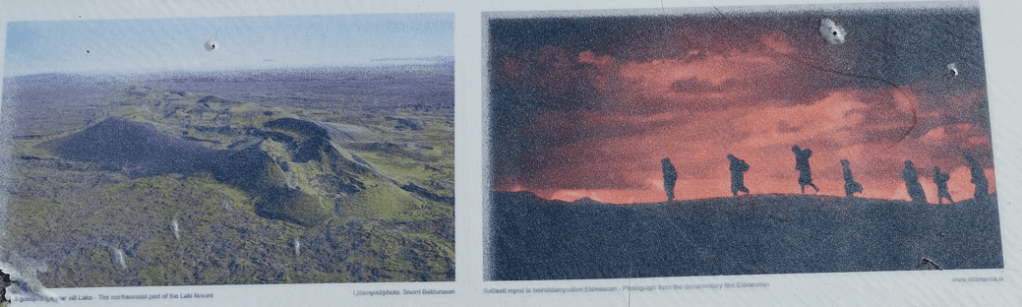

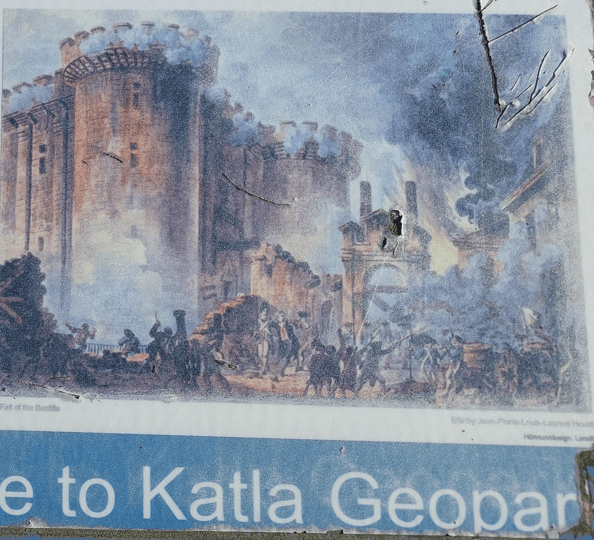

Along the Ring Road, informational displays describe the severe consequences of the 1783 Laki eruption. Images depict the suffering experienced by the Icelandic population during the event. Another image refers to the French Revolution, illustrating the wider climatic and societal effects of the eruption.

The volcanic haze produced by Laki spread across large parts of Europe, contributing to crop failures and famine. These environmental stresses intensified social tensions in France and are considered one of the contributing factors to the unrest that culminated in the French Revolution.

These two eruptions are did affect the history of Iceland more than any other volcanic events.