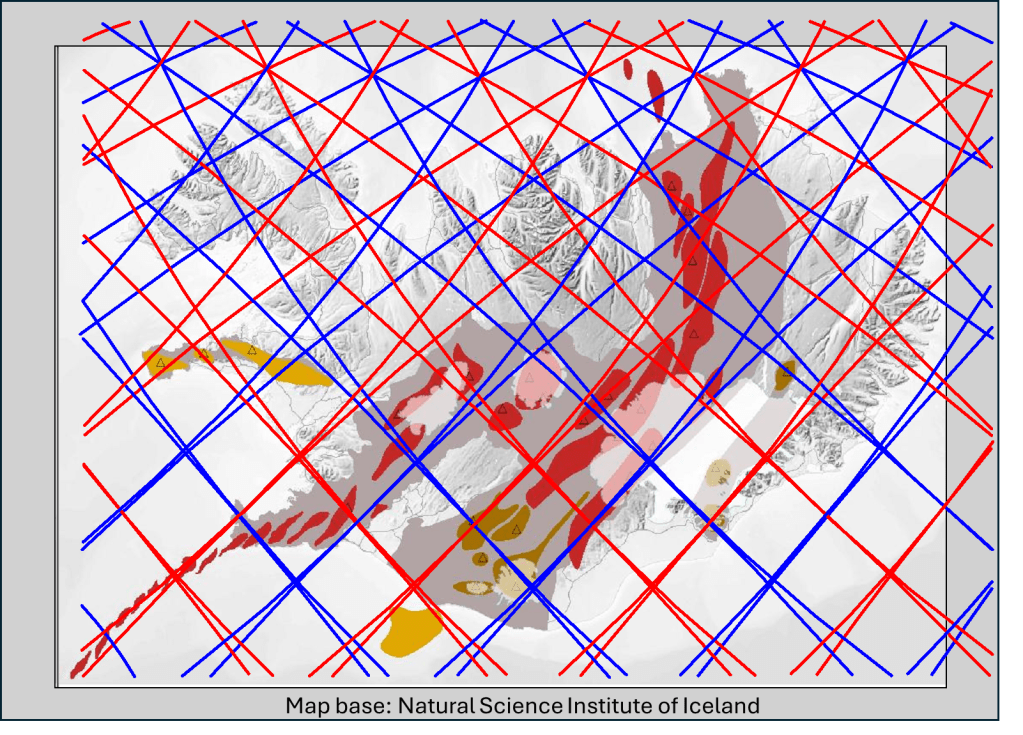

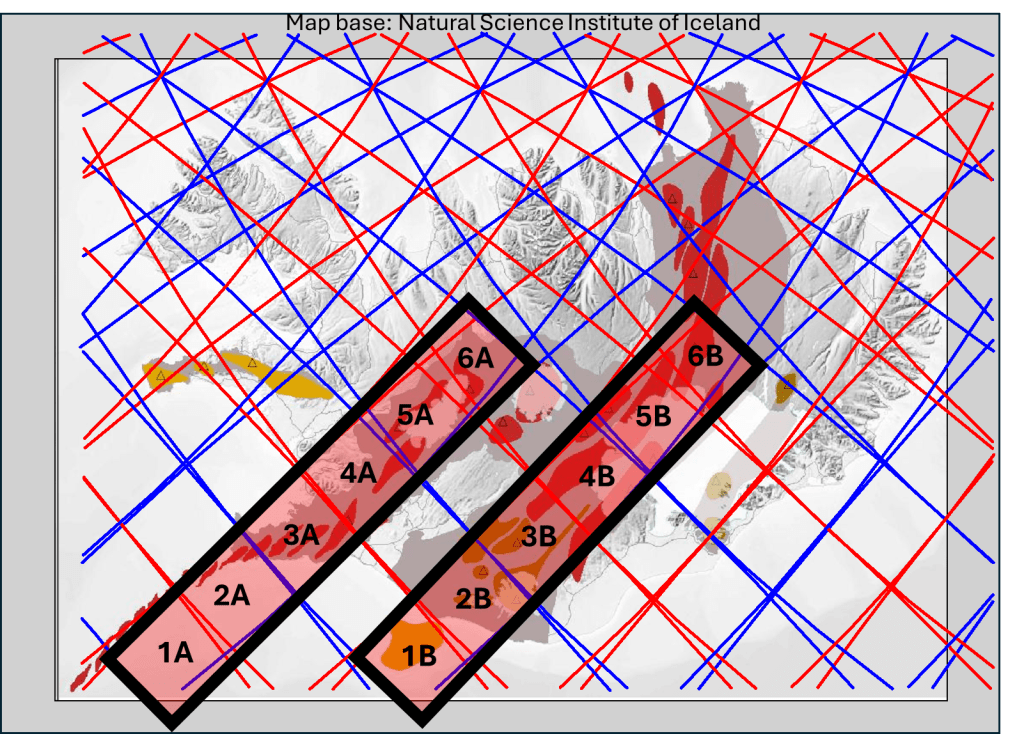

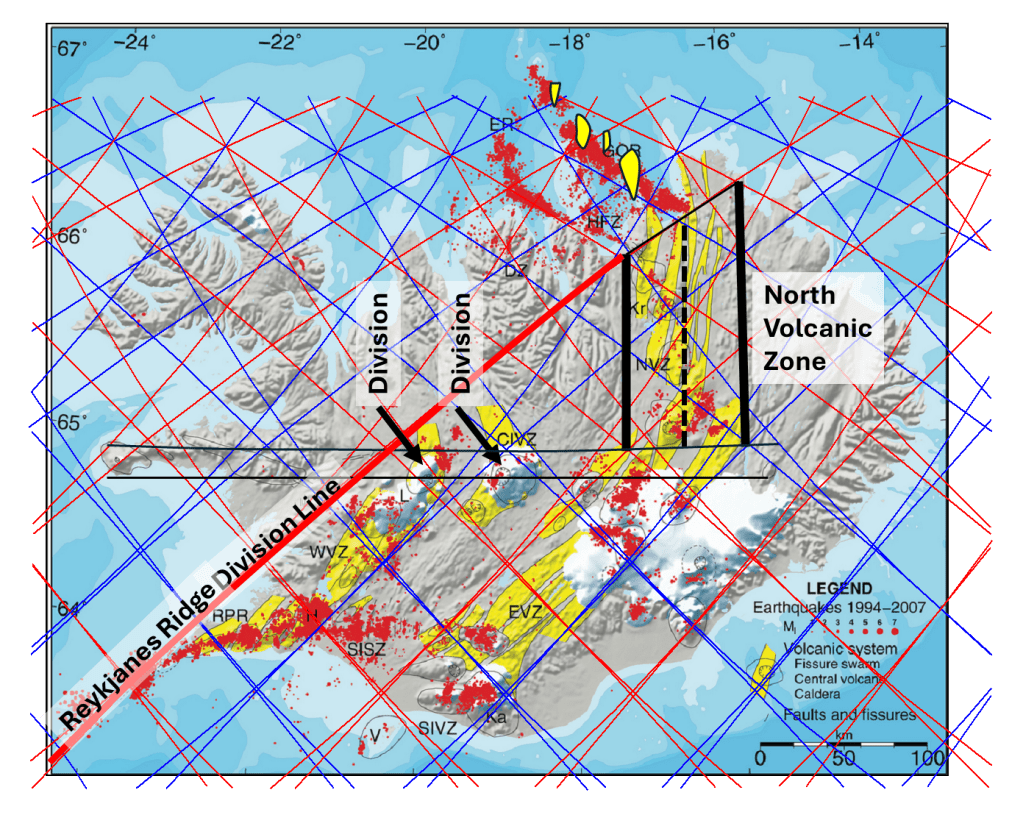

Iceland comprises several volcanic zones that partially intersect and overlap. One of these, the North Volcanic Zone (NVZ), is distinguished by a generally north–south alignment, expressed through en-echelon volcanic systems and long fissure swarms that extend both northward and southward beyond the traditionally mapped limits of the zone.

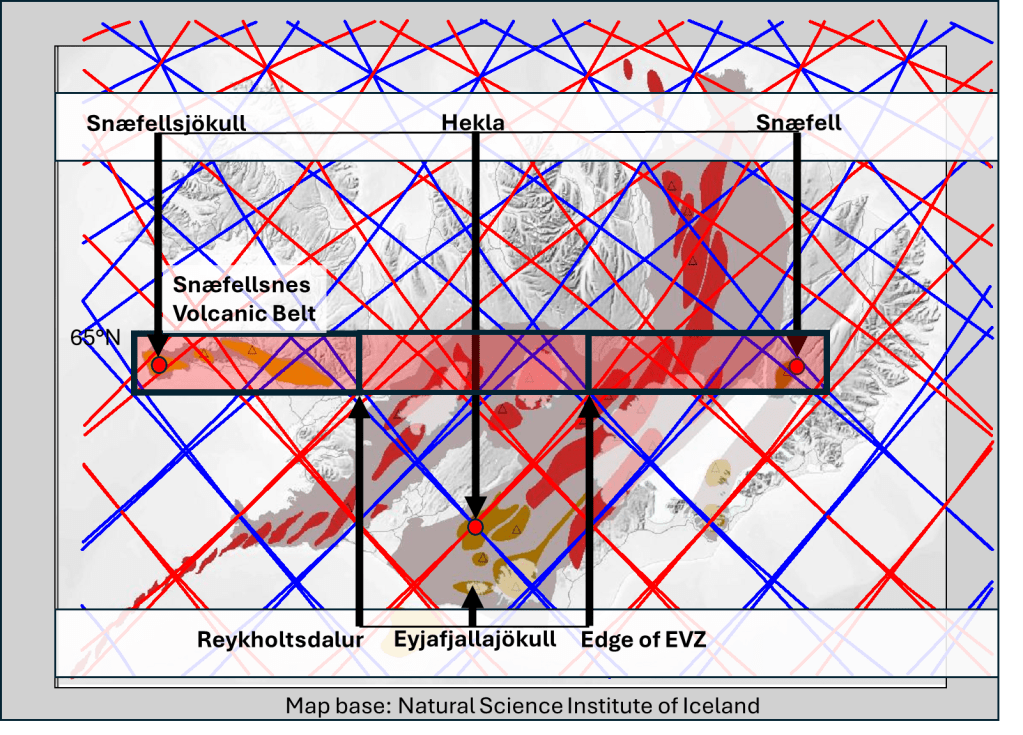

When interpreted within the framework of the Mantle Convection Rolls Model, the NVZ can be defined with comparatively high geometric precision. A key reference is the Reykjanes Ridge division line, which can be extended mathematically across Iceland. This line intersects the terminal regions of the Tjörnes Fracture Zone, coinciding with the eastern limits of the epicentral swarms associated with the Húsavík–Flatey Fault Zone and the Grímsey Oblique Rift. The same division line also marks the termination of the Reykjanes Peninsula Volcanic Zone, where it merges with the Reykjanes Ridge itself.

At the southern end of Iceland, a second well-defined boundary occurs near 64.9° N, within a narrow latitudinal band south of this line. Here, a pronounced and abrupt change in volcanic and tectonic alignment is observed, involving the West Volcanic Zone, the Central Iceland Volcanic Zone, and the sharp bend separating the NVZ from the East Volcanic Zone.

Taken together, these two geometrically and dynamically constrained boundaries imply that the NVZ can be defined with high precision as the volcanic domain bounded to the south by approximately 64.9° N, and to the north by the Reykjanes Ridge division line intersecting the terminal epicentral swarms of the Húsavík–Flatey Fault Zone and the Grímsey Oblique Rift.

In this study, volcanic zones are defined exclusively on the basis of volcanic architecture and mantle-scale organization, rather than seismic fault systems or plate-boundary kinematics.