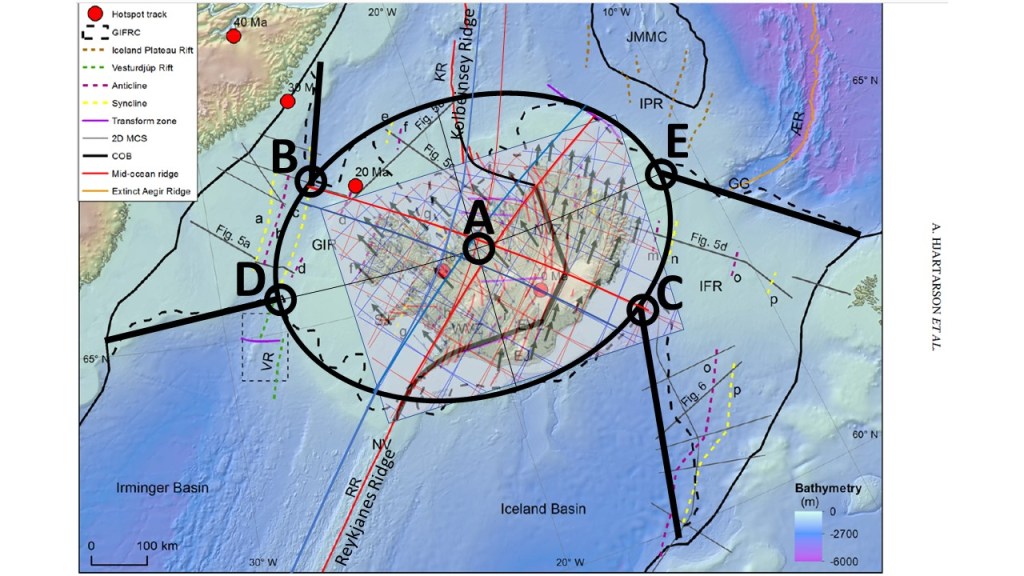

The ridges connecting the Icelandic Plateau with Greenland and the Faroe Islands are equidistant from a single point in central Iceland. This can be seen in the map below:

The basic map is from https://sp.lyellcollection.org/content/447/1/127/tab-figures-data

On the base map, the elliptical outline of the Icelandic Plateau has been added, with its central point marked as A. The locations where the Greenland–Iceland Ridge and the Iceland–Faroe Ridge meet the ellipse are marked as B and C; both lie at equal distances from point A. Similarly, points D and E, defined along the ellipse, are also equidistant from A.

When the bathymetric extensions of the Reykjanes Ridge and the Kolbeinsey Ridge are traced, they also converge toward point A. Thus, if we normalize the surrounding topography relative to the elliptical form, all of these ridge systems ultimately meet at a single focal point: A.

It is notable that points D and E lie on the same latitude, while B and C fall along the same meridional division, reinforcing the symmetry of the structure.

The Icelandic abyss appears to have developed gradually into a remarkably precise elliptical form. This ellipse is oriented exactly east–west, with its major axis defining the long dimension of the Icelandic Plateau.

When the outline of the ellipse is compared with surrounding ridge systems, the symmetry is striking. The Greenland–Iceland Ridge and the Iceland–Faroe Ridge both coincide with the ends of the major axis. The other two margins align with features that reflect mirrored convection rolls relative to those of the Reykjanes Ridge. In other words, the abyssal form not only echoes the geometry of the connecting ridges but also mirrors the mantle dynamics that created them.

Eliminating the strong bathymetric influence of the Reykjanes Ridge and the Kolbeinsey Ridge, the elliptical outline becomes nearly perfect. Yet this geometric precision has largely gone unnoticed, perhaps because attention has traditionally been focused on local volcanic and tectonic features rather than the broader structural form of the abyss.

The symmetry becomes even more compelling when viewed along the central meridional division through point A, the ellipse’s geometric center. This line passes directly through the craters of Hekla and Eyjafjallajökull — arguably Iceland’s two most famous volcanoes. Moreover, if the axes of the Reykjanes Ridge and the Kolbeinsey Ridge are extrapolated inland from the seafloor, both converge at point A as well.

Such a degree of geometric and geodynamic coincidence is unlikely to be accidental. It suggests that the Icelandic abyss represents not only a surface plateau but also the expression of deeper, organized mantle flow. Explaining why this elliptical form has persisted — and why it has been overlooked — remains an important challenge for understanding Iceland’s unique geodynamic setting.